|

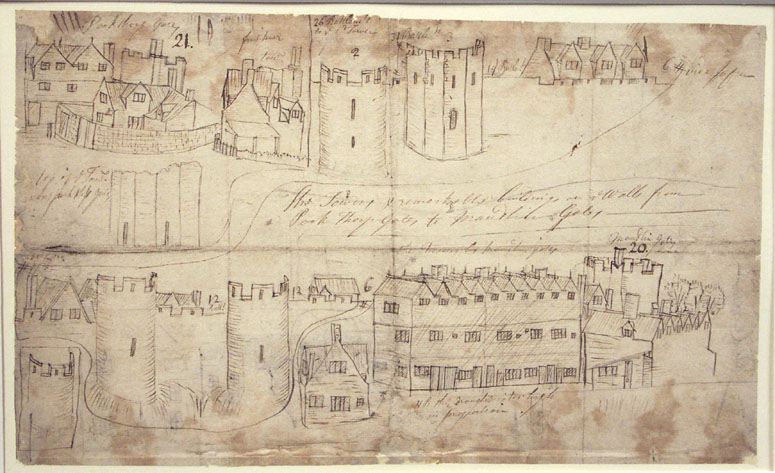

[2] Detail of a sketch by John Kirkpatrick about 1720 that appears to

show the first tower on the river bank. [Norwich

Castle Museum and Art Gallery 1894.76.1746:F]

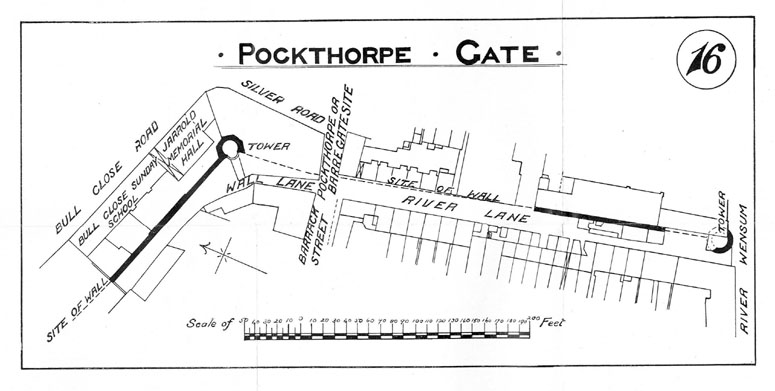

[3] Map of River Lane published in the report of 1910.

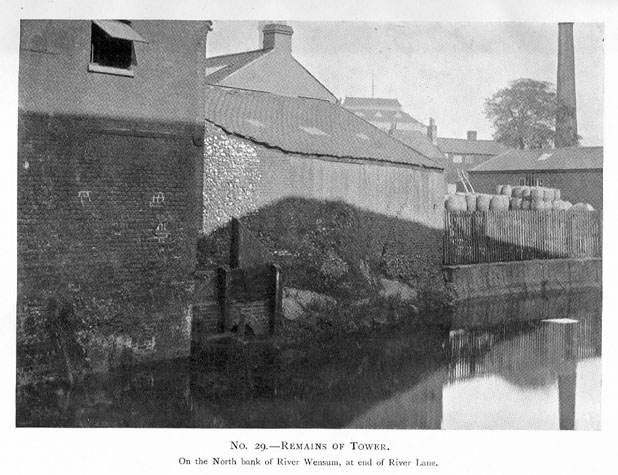

[4] The remains of the tower from the river in 1910.

[5] The remains of the tower on the river bank from the north.

[6] The south end of the wall from the west with part of the tower to the right.

[7] The remains of the south-east corner of the tower from the east.

[8] The south end of the wall from the south west with the surviving parts of

the tower to the right.

[9] The south part of the wall from the north east.

[10] Inserted doorway between sections showing the brickwork of

the south jamb from the north east.

[11] The main section of the wall from the north east.

[12] Low brick wall between the main sections of the surviving

wall from the south west.

[13] The north end from the south east.

[14] Area of damage to the facing flint work on the inside of the wall.

[15] The north end of the surviving wall from the north.

[16] The north end of the wall showing damage and dislodged flints.

|

Historical Background Report

Summary

Documentary evidence suggests that the flint wall

at River Lane was the last section of the city walls to be built with work still

in progress in the 1340s. Presumably this delay, in part, reflected the

disputes between the Prior and the citizens of Norwich as the north-eastwards

expansion of the city boundary encroached over land at Pockthorpe owned by the

Abbey.

None of the surviving documents refer to the tower

on the river bank and it is still unclear if the wall and tower were built at

the same time. Although they are probably contemporary, the tower could

pre date or post date the wall. From documentary evidence and from

historic maps It would appear that the tower was circular matching the Boom

Towers and the towers at Oak Street and above Heigham Gate where the walls there

terminated on the river bank. There is no structural or documentary

evidence to indicate how high the tower was it may have been the same height

as the walls with just a lower chamber like many of the other intermediate

towers or it may have had an upper chamber.

Nor is there evidence to indicate that there was

ever an arcade on the inner side of the wall to support a wider wall walk.

It may be significant that neither the wall down to the tower on the river bank

at Oak Street [Report 13] nor the wall running down to the west Boom Tower at

King Street [Report 36] had inner arcades. Even without the arcade, there

would have been a narrow wall walk with a high parapet on the outer side.

Access to the wall walk was probably from the upper chamber of the gate.

The gate appears to have had a staircase on the south side abutting the lost

north part of this section of the wall. The section certainly had

battlements with widely spaced embrasures. Documents record that there

were 40 merlons in a length of just over 105 metres. Surviving merlons at

Ber Street and Carrow Hill are also about 2 metres wide with embrasures about

300mm wide and with intermediate loops in the centre of each merlon.

Documents also show the importance of the lane

inside the wall. The city authorities specifically acquired land to create

a clear way down to the river from Pockthorpe Gate. Again there were

similar lanes down to the river on the inner side of the wall west of Oak Street

and on the inner side of the wall below King Street. The lane may have

been seen as an important clear way for moving troops but more probably there

was a deliberate attempt to keep buildings back from the inner face of the wall.

Presumably roofs of buildings against the wall would have been vulnerable to

incendiary attacks from outside and buildings against the walls may well have

been seen as a potential means for smuggling people or goods in or out of the

city when the gates were closed.

General description of the historic fabric

The standing fabric of the wall is essentially

medieval for original putlog holes lined with bricks survive in several areas.

However, only core work survives and that much re-pointed and refaced. The

face flints were lost when buildings constructed against the wall on both sides

in the 18th and 19th centuries were demolished. The present ground level

may be somewhat higher than the medieval level but none of the descriptions of

work undertaken around the walls in recent years suggests that there is any

buried evidence for arches.

There appears to be nothing in the way that the

wall is constructed to distinguish it from other earlier sections of the wall

elsewhere.

Documentary evidence:

Work on the gate itself was,

presumably, in progress in 1338 for a document of that year records that William

de Claxtone, Prior of Norwich, gave one great plank to 'Barrechate' which

cost 4s. and gave 40d. and 12d. to the workmen there. [Comp. Cam.] If the

gateway was still not completed, this would explain why in 1342 Pockthorpe was

not one of the gates that was armed with 'espringolds' paid for by Richard

Spynk.

In 1344/45 John, son of Robert de Kirkeby, granted

and sold to the city one piece of land out of his close in St James' parish at

Barregates. This land lay between the land of the Communality to the east

and his land to the west containing in breadth 14 feet and in length as much as

his said close extended. [Civ. Dom. Quoted by Fitch] This land may

have been on the north side of Pockthorpe Gate. However, on the Feast of

St Mark (25th April) in 1346 Richard de Lyng, parson of Redham, John de Berneye

and John Chenele granted a piece of their land at Le Barregates for the wall and

lane there. The land stretched from the King's way to the King's river

called Wensum. [Dom. Civ.] Presumably, this land was required to complete

the building of the wall from the south side of the gate to a tower on the bank

of the river.

A Customs' Book dating from the 14th century,

from the reign of Edward III, records the number of battlements in the circuit

of the defenses. The wall and towers north of the gate, between Pockthorpe Gate

and Magdalen Gate, had 178 battlements, Pockthorpe Gate had 10 battlements and

the wall and tower to the south of the gate about 40 battlements.[Fitch

page x] Again, this list was presumably compiled to help decide what

repairs were required and to determine who was responsible for the work.

In the 15th century there were further disputes

about the responsibility for repairs to each section and in 1451 an Agistamentum

or distribution of the burden of repairs was issued. Fibrig ward was

responsible for Fibrig (Magdalen) Gates 'with al the walles and toures unto

the next tour on the north side of Barre Gates.' East Wymer Ward on the

south side of the river 'shall have the said toure and Barre (Pockthorpe)

Gates, and alle the walles unto the toure in the water, and the same toure; with

the dongeone by ye Hospitall Meadowes on the north est corner.' [Fitch

page xvii and The Agistment for the Walls, 1451, 1481, Liber Albus, f. 177;

Hudson & Tingey, vol. II, pages 313-5]

Blyth's 1842 Directory of Norwich mentions that

the wall here `extends to the river side, where it finishes with a round

tower.' [Blyth, page 5]

Map evidence:

Although Cunningham's map of 1558 shows the wall

between Pockthorpe Gate and the river, he does not show the tower on the river

bank. By the mid 16th century there were houses on both sides of what is

now Barrack Street inside the walls and on both sides of the road outside the

gate. However no buildings encroached on the wall. Kirkpatrick in

the early 18th century also shows the wall free of buildings. He shows a

round tower on the river bank and appears to show the outer ditch still with

water in it for he draws a stream running away from the ditch just south of the

gate ran parallel to the river before it joined the main channel on the outside

of the bend opposite Cow Tower. Cleer, on his map of 1696 also marks the

stream and the tower. Perhaps the stream suggests that the low lying land

was potentially wet or waterlogged. Certainly if the river was wider in the 14th

century, marshy land here beyond the ditch would have provided additional

defence to this section of the wall.

None of the 18th-century maps, including those by

Hoyle, Blomfield and King show the tower though they all mark the wall surviving

for the full length between Pockthorpe Gate and the river. Hochstetter in

1789 showed a large courtyard house built against the outside of the wall

immediately south of the gate. Clearly the ditch and stream had been

filled in by then although a number of narrow channels are shown draining the

gardens along the north bank of the river beyond the wall. Hochstetter

also shows two long narrow buildings against the inside of the wall at the south

end, over the line of the inner lane. The brick fireplace and chimney of

the building furthest from the river survive.

Both buildings are shown on the first edition of

the Ordnance Survey map of 1885 [sheet LXIII.11.9] but by then there were houses

against the whole of the outer side of the wall. The north end of the wall

had been demolished and only the surviving section is shown as still standing in

1885. The tower on the river bank is marked and is shown as being built

into the south gable of the building on the inner side of the wall. River

Lane is marked on that map as Water Lane.

Historic views and historic photographs:

A sketch of the walls around Pockthorpe Gate drawn

by John Kirkpatrick about 1720 and now in the Castle Museum, may include a

depiction of the tower on the river bank. The drawing has a number of

vignettes of different towers from several different directions. One is

labelled as the first tower and a separate tower, clearly polygonal is

presumably the surviving tower at Bull Close Road. [Norwich Castle Museum

and Art Gallery 1894.76.1746:F] [2]

There appear to be no other historic topographical

views of the tower or this section of the wall. The 1910 report by Collins

includes a photograph of the tower taken from the river but it is dominated by

the industrial buildings running down to the river bank and it is difficult to

distinguish which parts of the flint wall that can be seen, belong to the tower.

The sketch plan with the report shows a much more substantial part of the tower

standing with an arc of wall on the south-west side. It may have stood to

almost its full height as the flint work on the photograph appears to rise to

the level of the eaves of the adjoining building. [3 & 4]

[Collins,

1910 photograph 29 and map 16]

Archaeological reports:

The site has been of recent archaeological

interest and is mentioned several times in the Sites and Monuments Record

(hereafter SMR). SMR site name NF736 shows an Elizabethan coin found in a small

garden by the city wall in 1983, while site name NF178 mentions a modern shed

built along the west side of the medieval city wall.

In 1987 a trial excavation undertaken by the

Norfolk Archaeology Unit for Anglian Water revealed that parts of a turret next

the River Wensum (23563 09305), and visible above ground, were of modern

construction. However, they overlay the remains of a turret with an

entrance doorway dressed in brick with a brick-on-edge threshold (SMR779). Also

revealed was the constant refacing of the city wall, which has given a false

impression that the wall steps inward, when excavation shows it continues in a

straight line (23563 09307). The wall extends to a depth of about 2.3

metres at a point 20 metres north of the river (23553 09340). Apparently a

secondary file exists detailing these finds, but it could not be located at the

NAU or at Gressen Hall at the time of search.

In 1988 digging by Eastern Electricity for a cable trench, running south of the

footpath approaching River Lane, cut the line of the city wall 3.25 metres south

of the south curb edge. This revealed that the top of the wall was only 5cm

below the surface of the tarmac. The interior (west face) was visible, and

dressed with facing flints, while the exterior (east face) was obscured by later

abutting brickwork. The width of the wall was found to be 1.20 metres,

with 60cm depth visible. The bonding agent was found to be lime mortar.

Approximately 60cm of wall depth and 80cm length was destroyed for the cable

duct (SMR NF819). Apparently plans for the location of the wall are kept in the

associated River Lane File, but this was not located at the NAU, nor at Gressen

Hall at the time of search.

Condition Survey

There are four wedges or chunks of flint wall on

the river bank forming the north part of the curve of the tower. [5] These

are cut through by the pathway of a river-side walk running east west. The

surviving wall runs back from here for 50 metres. The tallest section

close to the tower is 4.5 metres high but much of the rest is much lower some

parts being little more than 300mm high.

Essentially, there are five sections to the wall

[external and internal elevations 01-03 & 01-04].

The first part is the 'remains' of the tower

itself. These stand on the embankment about 1.25 metres above the level of

the river. The three detached blocks are of irregular shapes but basically

wedges none more than 1.8 metres high. [6 & 7] They form a curve

representing the north side of the tower. A pathway runs between the

blocks but generally they are in a good state of repair and not threatened by

the relatively small number of people that must use the path. The flint

work all looks modern. It is difficult to be certain what is being

measured but if the flintwork above ground does respect the original plan of the

tower at a lower level, then the tower was 6.3 metres across and had an internal

diameter of 4 metres. [south elevation of the tower 01-05]

The fourth part of the tower is an integral part

of the first section of the wall. [8] This is just over 5 metres long and

is the highest part of the surviving wall being over 4.5 metres. The wall

has been almost completely rebuilt and is ostensibly brick faced on the east or

outer side. The brickwork is mainly headers interspersed with flints

though there is a string or band of modern brick across the upper part

presumably to strengthen or consolidate the wall. The inner or west side

is almost completely covered with undergrowth though one putlog survives at an

upper level and the position of this lines up with putlogs further along the

wall. Most of the flints here are cobbles rather than knapped flints which

generally around the walls indicates an area of repair. Ivy over the wall should

be removed and dense bushes on the east side thinned out. Vegetation on

the top of the wall should be removed and any hollows or areas of missing flints

should be repaired or replaced. Soft mortar on the top should be replaced

with a soft lime mortar laid to encourage water to run off.

The third section of the wall has been completely

rebuilt mainly with cobbles and forms a low retaining wall for a clad industrial

building against the east side that sits on the wall. This was said to

have been built in 1972.

The fourth section is much more substantial and is

distinguished by incorporating the remains of a fireplace and chimney stack

built against the wall when a building was constructed against the west side of

the wall in the late 18th-century. The wall here is in a very poor state

with large areas of mortar on either side of the stack that are just

interspersed with flints and bricks. The area is de-laminating and some

immediate repairs are required. The upper part of the wall has more

regular courses of brick that form a copping. High buildings around

provide some shelter from wind-driven rain but this section is still very

vulnerable to damage from water penetrating the exposed core. Self-seeded

buddleia on top of this section should be removed and the top of the wall

consolidated. At the north end of the part there is a narrow gateway or

doorway with a brick jamb on the south side. [9 & 10] This too is a

surviving part of the 18th and 19th-century buildings constructed against the

wall. Bricks on the east side at the jop of the pier have collapsed and

this should be rebuilt.

The last and longest section is heavily overgrown.

[11] It drops down in the centre to almost ground level with brick on the

west side. [12] It rises up again to just under 3 metres high before

stepping down again and tailing out at a point 50 metres from the river.

On the west side are vertical piers of brick work that are stitched into the

flint and are presumably reinforcements possibly where cross walls of the later

buildings were demolished. The east side of the wall is all exposed core

work. Though generally well pointed some large areas are breaking away.

[13 & 14] The wall here is at most 790mm thick the wall excavated

to the north, close to the site of the gate, was 1.2 metres thick and the

archaeological excavation reports suggest that the buried parts are even more

substantial. Possibly 200mm of facing flint on both sides has been lost.

The top of the wall is very irregular and water

penetration is a serious problem. Curiously, the dense undergrowth of ivy

climbing over the wall may provide a level of protection. In some areas a

hard cement mortar has been used. In any repairs this should be replaced

with a softer lime mortar.

The low north end is breaking apart and should be

rebuilt reusing the bricks and flints. [15 & 16]

List of known repairs:

It is not clear how much repair work was

undertaken in 1972 or 1987.

Summary of present condition:

Some areas of the flint work are in a very poor

condition particularly at a low level at the very north end where flints are

breaking away, along the top of the north section which is very irregular and

around the chimney stack on the west side.

Principal conservation problems:

There are no serious problems with this section of

wall although it should be monitored annually and areas of loose core work

re-pointed. There are three general problems:

- Shedding flints on the face and top of the wall

Water penetration into the mortar particularly

where the core of the wall is exposed along the broken irregular line of the

top.

- Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

The roots of plants such as buddleia and ivy break

into the mortar causing initially shedding of single flints but rapidly root

stocks of larger quick-growing bushes create deep fissures. Although the

gardens around this section are well maintained there are nevertheless several

self-seeded buddleia bushes on the wall top.

Deterioration of the brickwork

Several areas of the wall have been refaced with a thick buttering of mortar

with random coursing of reused and widely spaced bricks and flints. This

is presumably material from the demolished buildings against the walls reused to

consolidate and repair the standing wall. If areas are repaired then the

bricks should not be reused. On the west side the piers of brick are now

an archaeological feature telling part of the history of the wall and should be

retained

|