|

[6] The inner side of the wall from the south

west looking towards the site of Magdalen Gate.

[7] The east end of the wall showing clearly the parapet walk.

[8] Detail of the upper part of the archway from the inner or south

side.

[9] The open archway from the south west showing the deterioration of

the flintwork on the east side.

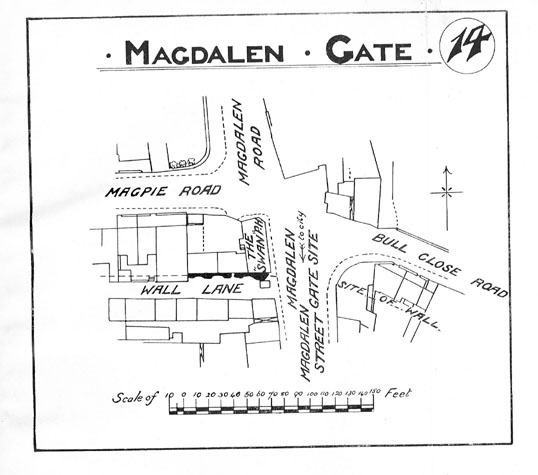

[10] Map of the wall in 1910 from the report by A Collins.

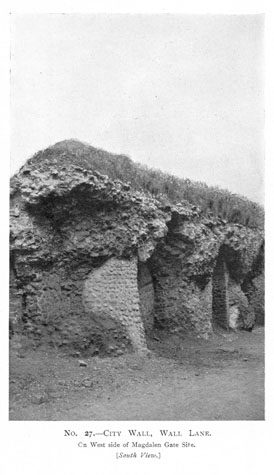

[11] The wall in 1910 published in the report by A Collins.

[12] The archway from the outside.

[13] The partly blocked and rebuilt arch to the west of the open

archway.

[14] The arch at the west end of the wall on the south or inner side.

[15] The outer face of the wall between the archway and the blocked

doorway

|

Historical Background Report

Summary

This section of the wall is

significant because it retains much of the inner arcade and because it abutted

one of the main gates into the city. Although the arcade is in a poor

state of repair, it shows clearly several important elements of the construction

of the wall. [6] The arcade supported a wider wall walk and was

constructed with shallow pointed arches with two or three rows of headers. [7

& 8] These arches were relatively widely spaced with two levels of

brick-lined putlog holes in the centre of each pier. These indicate that

the main part of the wall was raised in three stages or lifts. With bricks

lining the putlog holes, scaffold timbers could be taken out and moved up for

the next stage. The parapet would, presumably, have been built as a fourth

lift.

The area of flint wall surviving

at the east end, closest to Magdalen Street, is wider than the intermediate

piers. As elsewhere, the first arch after a gate or an intermediate tower

was set further out than the width of the intermediate piers. The space

above was where there was an inner parapet to the wall walk here and steps up to

the upper chamber of the gate.

At Magdalen Street the first

arch appears to have been slightly taller and slightly wider than the following

arches though there is no obvious reason for this. [9]

The wall is set back 16 metres

from the edge of Magpie Road which roughly defines the width of the outer ditch.

The road is on the line of a lane outside the ditch but is presumably wider than

the lane having encroached over the outer edge of the ditch.

On the inner side of the wall

the line and level of the medieval lane inside the wall survives.

Documentary evidence:

There are no surviving medieval

or later documents that appear to relate specifically to this short length of

wall.

Map evidence:

The early maps of Norwich

provide little evidence that is relevant to this section of the wall although

Kirkpatrick does show that by about 1720 there were long narrow buildings

against the outer side of the wall on both sides of Magdalen Gate. These

were presumably built over the line of the ditch which must, by then have been

filled. Although, curiously, Hochstetter in 1789 shows this section of

wall clear of buildings on the outer side, he shows the first intermediate tower

of the wall between Magdalen Gate and St Augustine's as being very close to

the west end of this section. Plot boundaries, that in part survive,

suggest that it was probably between the west end of the main section and the

small fragment of flint wall surviving in the back yard to the west. This

would fit with the arrangement that survives at St Stephen's where the towers

on either side of the gate were placed relatively close to the gate. This

would have provided cover to the approach to the gate where the causeway or

bridge before the gate made it vulnerable to an attack from the sides. It

may be significant also that Hochstetter implies that the tower west of Magdalen

Gate was circular. Many of the intermediate towers were semicircular and

open to the back. However, the towers flanking St Stephen's Gate were

enclosed or partly enclosed and vaulted. Presumably this provided a more

substantial upper platform at the level of the wall walk or above for fighting

troops, particularly for archers covering the outer approach to the gate.

The first edition of the

Ordnance Survey map of 1885 [sheet LXIII.11.8] shows the inner side of the wall,

the line of the lane inside the wall, clear of buildings. However, there

is a building against the north side of the surviving wall. This was

around a courtyard open to the north and was identified as the White Swan Public

House. Presumably, it was the demolition of this building that damaged the

outer face of the wall. The map indicates that already the inner arches

were irregular. The blocked doorway towards the centre of the wall appears

to have been open and would have provided an entrance into the White Swan from

the inner lane. The arch at the east end that is now open was drawn on the

map as being closed.

Historic views and historic photographs:

The view of Magdalen Gate by

John Ninham shows the upper part of this section of the wall. The

embrasures of the battlement are shown widely spaced. [see above] A photograph

of the wall about 1910 was published in a report on the walls by Arthur Collins.

[Collins, 1910 plate 27] At that stage much more of the parapet survived

but the arches were already in a parlous state though much of the east side of

the upper part of the fourth arch survived. [10 & 11] This has now

gone.

Archaeological reports:

Work by the City Engineer's in

November 1957 uncovered part of the medieval wall behind number 134 Magpie Road

(the house immediately west of the yard with the fragment of wall. Notes

in the sites and monuments record [SMR NF261] record that the wall was about 7ft

(2.13 metres) from the back of the house and 6ft 9' (2.05 metres) below the

surface. It is not clear if it was the outer face of the wall that was 7ft

behind the house or the part that was uncovered.

Condition Survey

The surviving section of wall is

17 metres long and stands to a maximum height of 5.3 metres from the modern

ground level. It is at most 1.4 metres wide and has lost much of the inner

face of the wall where three arches of the arcade supporting the wall walk

survive. [Survey drawing of internal elevation 06-04]

The piers of the arcade have been rebuilt with cobbles forming rounded piers.

A photograph taken before 1910 [Report by Collins, plate

27] shows just how badly the lower parts of the wall had decayed and just

how much of the upper flint work of the arches was unsupported at that stage. [11]

Of the three arches the east arch closest to the road has lost most of its brick

work. As the piers broke back the bricks of the arches would have been

left unsupported and would have dropped out. [12]

The middle arch has been rebuilt within the last 30 years but soft bricks were

used with a hard cementitious mortar and water penetration from above has caused

considerable damage. [13] The arch will have

to be rebuilt within five years if the wall walk and remains of the parapet are

not to be undermined and threatened with collapse. What remains of the

third arch retains earlier brick but large areas of flint oversail the arch. [14]

The oversailing flint should be inspected annually to ensure that it is still

secure and safe and to monitor any problems with water getting in to the core of

the wall.

The wall walk and the broken

line of the surviving part of the parapet were restored in 1999/2000 and are now

in good condition. [Survey drawings of the east end and

the cross section of the wall 06-05 & 06-06] Water seems to be

running off the wall top well the most serious problem around the walls

generally is with water ponding on the top or entering the core through

setlement cracks or cracks caused by self seeded woody-stemmed plants.

Once water and frost damage starts, the damage to the top of the wall progresses

and accelerates as areas of flint are thrown out. Although the present

state of the wall top here is good the state of the wall should be monitored

annually and minor repairs or patching undertaken. Local people say that

the walls are used as a climbing frame by kids and flints are regularly

dislodged. If the toilet at the west end is demolished that will remove

one easy route up onto the wall top. This problem also highlights the need

to replace shed flints quickly to keep the face of the wall relatively level to

reduce the number of hand and foot holds.

On the north side of the wall

there is much evidence of the damage caused by demolishing houses that had been

built hard against the wall. [Survey drawing of the

external elevation 06-03] There are areas of protruding brick where

walls bonded in to the flint work have then been cut back, there is a doorway

with wooden lintels, now blocked, and areas of render or rough mortar with

widely spaced bricks and flints where lining out and plaster for internal wall

faces has been cut away. [15] The wall is

generally in a good state of repair following the recent restoration though

there are some obvious problems with the mortar mix used. There is heavy

leaching out of lime washed out by rain in some areas and the face is already

crumbling away in some areas. The precise mix of lime and sand and

aggregate should be assessed and the success of this repair monitored over

several years to inform what may be done next on other sections of the wall.

List of known repairs:

The wall was under scaffolding

in 1999 and 2000 when the flint work of the parapet was consolidated and the

outer or north face of the wall was repaired and re-pointed. Unfortunately the

face of the new work is already crumbling and breaking away and lime is leaching

out of the mortar mix with rain. The proportions of the mortar mix that

was used is not known but Brian Morton, when he inspected the wall, suggested

that it needed a hydraulic lime mortar mix with a correctly graded course sand. [see

brief note of visit in appendix] This area should be monitored and the

success of the repair assessed to help determine the most appropriate method and

mortar mix to use for repairs on other sections of the wall.

Summary of present condition:

Despite the extensive recent

repairs, there are still problems with the state of the wall. The wall top

is now presumably stable and throwing off water but the arches on the inner side

and the flint work at the east end need urgent attention.

Principal conservation problems:

- Decay of the flint work

On the south side of the wall

and at the east end flints are regularly shed or pulled away. As there

is a flint arch over the main footpath through the wall and as the flint on

the south side oversails the supporting piers, public safety is an issue here.

The wall should be monitored annually and if necessary an engineer's report

commissioned if the flint has to be tied back.

- Shedding flints on the top of the wall

Recent repairs make this less

of a problem on this section but the situation should be monitored regularly.

The wall walk here has a lip on the inner edge so there is potentially an

additional problem with water being held back and entering the core if it does

not run off quickly enough.

- Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

Plants and vegetation were

removed when the scaffold was erected a year ago but is already growing back.

Some plants may have self seeded but the probability is that roots were not

treated or removed. Generally for the walls some work needs to be done

on finding an appropriate herbicide and determining how frequently and how it

is to be used. Many people like the lichens and mosses that soften the

walls and give it a romantic ruin appeal. Buddleia and ivy do much more

damage much more quickly.

- Deterioration of the brickwork

The bricks in the arches have

deteriorated but as the flint work above oversails further damage can be

avoided by ensuring that water does not penetrate but runs off the wall

quickly.

|