|

[4] The outer face of the tower from the west.

[5] Base of arches on the inner or east side of the wall at the south end

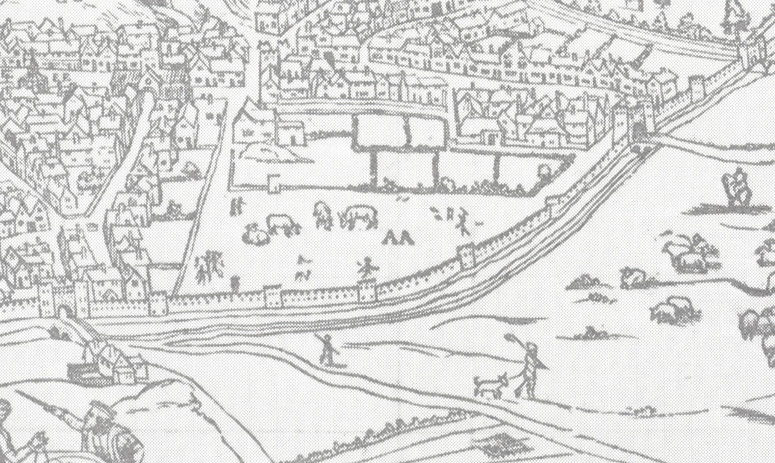

[6] Cunningham's Map of 1558 showing the city from the west. The

Chapelfield and Coburg sections of wall are in the foreground

[7] The tower from the south east in 1860 possibly drawn by David Hodgson.

[Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery 1922.135.FAW 93: F]

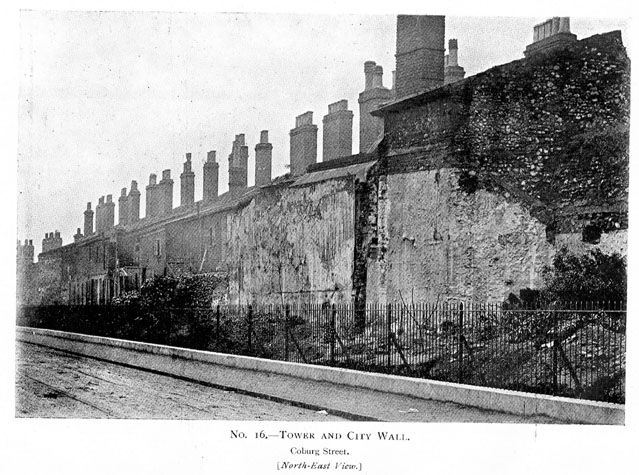

[8] Photograph of the tower and wall from the north east published in the

report of 1910.

[9] The north part of the wall from the outer or west side.

[10] The south end of the north section of wall.

[11] The north sections of the wall from the south west.

[12] The north end of the north section of wall.

[13] The ditch or outer side tower and the wall from the south west.

[14] View from inside the tower looking north through loop along the inner

face of the wall.

[15] The outer face of the wall north of the tower repaired with bands of

brick work.

[16] The north end of the wall from the north looking towards the

tower. The outer ditch was to the right.

[17] Section of wall buttressed with concrete on the outer or west side.

[18] The Tower from the south west.

[19] The city side of the tower from the north east showing the blocked

doorway with a hood mould on the east face of the tower.

[20] The blocked doorway on the east side of the tower from the inside.

[21] Remains of hood moulding over the blocked doorway on the east side of

the tower.

[22] Detail of secondary opening now blocked on the outer or west side of

the tower.

[23] The south side of the exterior of the tower.

[24] Detail of galetting on the south side of the tower.

[25] Detail of blocked loop and putlog on the south side of the tower.

[26] The outer face of the wall south of the tower surviving to almost the

full height apart from the parapet wall and crenellations of the wall

walk.

[27] Loop south of the tower on the exterior or west face of the wall.

[28] Loop south of the tower on the exterior or west face of the wall.

[29] The south end of the wall on the inner or city side looking towards the

tower from the south. The planting disguises where the ground level

was lowered and the footings of the wall exposed to create a level

pathway.

[30] The south end of the wall on the city or inner side looking towards the

tower. The wall was under built in brick where the medieval level

was lowered when the pathway and the dual carriageway on the line of the

ditch were constructed.

[31] South end of the wall with the remains of the base of an arch on the

inner or east side.

|

Historical Background Report

General description of the historic fabric:

To the south of Chapel Field East, following the line of what was

Coburg Street, at present the western edge of the Nestle Factory site,

there are five separate sections of wall between the south-west corner

of the park and the site of the gate of St Stephen.

[23-01 Map] There was an intermediate tower at the north end of this

section but that was demolished in the 18th century when the wall was

breached and a way through the wall created for the road now called

Chapel Field East.

[23-02 Plan] At the centre of the section are the remains of a substantial

two-storey polygonal tower, rounded to the outer side and three-sided

towards the city. [4]

At the south end, south of the tower, the bases of a number of

arches survive on the inner side of the wall.[5] These all supported a

wider wall walk that appears to have continued for the full length of

this south section as far as the gateway at St Stephens. The arches

and wall walk may not be a primary feature of the 13th-century wall.

Documentary evidence:

Because no documents have been discovered to date precisely the

construction of the flint wall and the towers in this section, it has

been assumed that, as elsewhere in the city, they were begun in the

late 13th century. However some references in early documents suggest

that part of this wall could be one of the first sections of the flint

wall to be built and may date from about 1253.

Parts of the Saxon and Norman settlement of Norwich were protected

by a ditch and bank and many of the principle streets were laid out

then so the site if not the structure of many of the gates may have

dated from the 12th century. Although the citizens of Norwich were

granted a licence by Henry III to enclose the city in 1253, it is

generally believed that the flint-built wall was not begun until the

raising of the first murage tax in 1294.[Fitch page v and page viii]

However, reference is made to a wall (not a bank or ditch) in Chapelfield

about 1256 (16th Edward I). In a Leet Roll from the 16th year of the

reign of Edward I (1255/1256) it was recorded that the millers of the

Prior of Buckenham had undermined the ditch between St Giles Gate and

St Stephen's Gate and 'made a purpressure under the walls.'

Purpressure generally refers to illegal enclosure or fencing in of land.

The Prior's mill was in 'Chapply Field.' [Fitch page 12]

Furthermore, in 1266 or 1267 John the Carpenter sold all 'his said

messuage lying near the Gate of Needham', (St Stephen's Gate)

to the Citizens and Commonality of Norwich, 'for their more

convenient building of the wall of the city there.' [Dom.Civ. quoted by Fitch page 12]

Throughout the medieval period the land here inside the walls seems

to have been open without buildings. Known as Chapel Field, it takes

its name form the chapel of St. Mary which stood on the site.

Blomefield notes that in 1402 this chapel was a meeting place for assemblies.

[Blomefield, page 119] In 1406 the citizens of Norwich 'claimed four

acres and an half of ground which belonged to Chapel in the Field ... lying

in Chapel-field Croft, within the city ditch, on which it abutted south...'

[Blomefield, page 124] This open area was much larger than the modern

area of Chapelfield Gardens and extended south almost to St Stephen's.

Blomefield cites the last leaf of the Book of Customs, which

notes that along this stretch of wall between St. Stephen's and St.

Giles gates were 229 battlements on the walls and towers. [Blomefield,

page 98]

The Norfolk Annals for 1852, compiled from articles in the

Norfolk

Chronicle, reports that on the 17th of April, pleasure gardens

now called Chapelfield Park were opened by the Corporation.

[Annals, volume I, page 11] An entry for 1867 explains that

after being closed for some months, the gardens were re-opened, with

'several portions of the city wall ... removed, and railings erected,

and efforts ... made to level the area'.

[Annals, volume II, page169] It is likely that that was the

stage when much of the wall between the Drill Hall [Report 21] and the

surviving tower in Chapelfield Gardens was demolished.

Map evidence:

Cunningham's map of 1558 is ostensibly a view of the city from

the west and shows clearly the wall between St Giles and St Stephen's.

[6] Both gateways are depicted with bridges before them, both with two

arches. The ditch in front of the wall is wide and appears to have a

considerable amount of water in it. The view shows just five intermediate

towers, all crenellated. It is impossible to make out any other details

although the two towers at the St Giles end appear to be flat towards

the outside ... that is of square or rectangular plan. All the sections

of wall between the towers have distinct arrow slits. The area inside

the wall is very open with cattle grazing. There are houses along the

north side of St Stephens and although Back St Stephens (now Coburg

Street) had been laid out, there were houses only on the south side and

the north side was open to Chapelfields.

By 1696, the date of Cleer's map, the open ground inside the walls

had been bisected by a lane on the line of the modern Chapelfield East

running directly up to the foot of an intermediate tower. There were

no buildings along the lane on either side and no buildings against the

wall itself either on the inner lane side or the outer ditch side.

'Chapply Field House'

on the east side of the plot was obviously a substantial property and

was set back from Chapel Field Lane, the extension of Horsemarket which

is now called Theatre Street, with formal gardens laid out to its north.

The map does not indicate a ditch on the outer side of the wall ... simply

lanes hard against the wall on both sides. The map shows only four of

the intermediate towers and certainly omits the southern horse-shoe

shaped tower that survives.

Kirkpatrick, on a map of about 1714 [Castle Museum and Art Gallery

NWCHM 1894.76.1682:F] marks just 5 towers between the gates. He shows

clearly both the polygonal tower and the horse-shoe shaped tower to the

south but omits a tower at the end of Chapel Field East. He shows two

towers on the west side of what is now the park and also the first tower

on the site of the Drill Hall at the north-west corner of the park.

There are still no buildings shown close to the wall on King's map of

1766 but one version of this map appears to show the tower at the

south-west corner of the park still standing. Hochstetter's map of

1789 shows the park much as it is now and still no buildings against

the wall itself. Sections of the wide ditch are clearly marked

particularly at the south end and it appears that the water in the ditch

was used for watering cattle before they were brought into the city.

The wall at the north end is not shown with a breach through it but

nor is the intermediate tower here shown.

Morant's map of 1873 shows houses built against the wall on the outer

side. The plans of these houses with their small yards and outbuildings

are shown in detail on the 25' Ordnance Survey map of 1883.

The plans of the houses against the wall are also reproduced in the

survey of 1910 [Report by A Collins, map 5]. The south end of the wall

was still standing so at least 15 metres of the wall has been lost since

1910. The 1910 plan also shows that the wall between the towers curved

inwards. It is not clear if this feature of the construction was

defensive, providing better sight lines between the towers, or

topographical, avoiding a ditch or drain.

Historic views and historic photographs:

An undated nineteenth-century water colour by Henry Ninham, 'Part

of the Wall by Chapelfield Gardens' [NCM 1054.76.94], shows a

doorway in the wall, with wooden door in situ, with brick edging to

the top of the arch. The inner mouldings are of stone. The wall is

visible to the right and left of the door, but not to the height of the

battlements. What appears to be a putlog hole is visible to the right

of the door. There is some ambiguity about the identification of this

drawing as another version in the Castle Museum is identified as being

in Bracondale.

There is a view of the polygonal tower from the south east in the

Castle Museum. [NWHCM 1922. 135.FAW 93.F] that shows the doorway on

the inner side still unblocked and presumably in use. It also shows a

square super structure on top of the tower with a gabled roof with the

ridge running north south. This appears to be secondary although there

is a doorway in the south gable at the level of the wall walk.

[7] Some of the surviving 14th-century documents for the repairs and

upgrading of the wall by Richard Spynk indicate that some of the gates

had thatched roofs. Is it possible that some of the intermediate

towers retained rather more vernacular features than the crenellated

battlements we might now imagine that they had originally?

The Archaeological Society at Garsett house holds copies of several

photographs of the Coburg Street wall with several showing major work in

progress. One is dated March 1908 and shows the arches at the south end

propped with timbers as the houses against the wall were demolished.

These photographs show clearly just how much of the wall collapsed as

the houses and buildings against it were removed. [8]

The Society also holds photocopies of a proposed guide to the wall

dated 1979.

Archaeological reports:

An excavation at 42 Chapelfield Road in 1972 by J Roberts for the

Norwich Survey examined the nature of the city wall foundations.

Trenches, dug at right angles to the city walls, revealed that the

foundations were very shallow, and had been cut into natural sand.

The fillings of the city ditch along this stretch of wall were found

to be rubble that dated from the late 18th- to 19th-century.

[SMR NF236]

An excavation for a sewer by the City Engineers, for 44-58 Chapelfield

Road immediately to the north of this section, prior to the construction

of the ring-road in 1973, took place within the fill of the city ditch.

The excavation revealed that the fill was mainly of foundations and

modern demolition/backfilling. [SMR NF196]

In 1974, sewerage trenching operations in front of 60-102 Chapelfield

Road were carried out outside the city wall in advance of constructing

the inner link dual carriage way. This work extended north-east to

south-west along the outer side of the city walls and revealed

'Disturbance almost wholely of the 18th century - 20th century

for houses backing onto the city wall with rubble from their demolition.

[SMR NF196]

In 1975 an underpass for the inner link road was dug from inside the

city wall to the west pavement of Chapelfield Road. [SMR NF260] No trace

was seen in this section of the defensive ditch.

SMR NF372 gives a full account of the transition of the area,

and a secondary file exists, but does not contain much information of

use which is directly relevant to the walls or towers in this area.

A Department of the Environment Report [HSD9/2/1005 part 6 contained

in Gressen Hall file 384] mentions maintenance work to be carried out

on the section of wall and towers from Chapelfield Road North to St.

Stephen's Gate in 1988.

CONDITION SURVEY

List of known repairs:

Not available at this stage. Photographs in the NNAS collection

at Garsett House shows the tower with extensive scaffolding.

Presumably this was taken when the surrounding houses were demolished.

Certainly extensive work was required then to consolidate and stabilize

the walls.

Summary of present condition:

The first two sections of wall at the north end are short and both

are in a poor state of repair [23-04 Ext Elev]... both lean outwards markedly.

[9 & 10] The first section is 3.2 metres long, just 3.6 metres

high and only about 1 metre thick. After a gap of 4.5 metres,

the second section is 6.6 metres long, 4 metres high and about the

same thickness as the first section. [23-05] Both sections have been

extensively cut back and damaged by the building and subsequent removal

of houses hard against each side. [11 & 12] The map of this section

of the wall published in 1910 shows the houses and their arrangement

clearly. Numbers 60, 62 and 64 Chapel Field Road were on the west

side and 73 Coburg Street was against the inner side of this section

of the medieval wall.

The level of soil on the inner side of the wall has been lowered by

between 200 and 400 mm to allow for the narrow passageway of the

footpath between the wall and the north gateway of the factory. [23-04 Int Elev]

Bricks and rubble have been inserted below but archaeological excavations

in this area have shown that the medieval wall had very shallow foundations

and presumably there is little or nothing below these sections of wall

to provide support.

After a gap of just over 16 metres, now occupied by a bus stop with

footpaths running down at angles from the main road to the inner

footpath, is the main section of wall. This is just over 71 metres

long and includes, approximately at the centre, the substantial remains

of a polygonal tower.[13]

The section north of the tower has evidence for a series of loops

which are widely spaced with about 6 metres between each loop. This

suggests that there were no arches on the inner side to support a wall

walk. The wall has little facing flint work on the inner side and

much of the core work is exposed. There are no areas of brick arch

surviving and there is no disturbance or obvious rebuilding at the

junction of the inner side of the wall and the north side of the tower

that would indicate that an arcade has been demolished. A surviving

loop in the north wall of the tower, that looks along the inner side of

the wall would also suggest, from its position, that there was no arcade

here. [14]

On the outer side much of the flint work has been repaired. At the

end of the 19th century there were houses all along the outside ... numbers

78 and 80 Chapel Field Road were built close to or hard against the wall

with narrow yards to the rear and outbuildings built against or into the

wall. This section is distinguished by an area of rebuilt wall with

brick quoins and strings forming a panelled section 4.6 metres long and

4.2 metres high. [15] This form of repair and strengthening of the face

is a technique used in vernacular domestic buildings and is found

elsewhere in the city.

Most of the facing flint on both sides at the top has been lost

although the top of the wall is in a relatively good state of repair

with few flints being shed. Presumably, this is the consequence of

good repairs in the 1980s.

The north end of the wall, however, is in a dangerous state. It

is very thin where the facing flints have been lost and the wall here

is less than 800 mm thick. More serious, where the pathway has been

cut down on the inner side of the wall the base has been undermined.

This is also the section of wall closest to the roadway itself and

presumably the wall is effected badly by traffic vibration. It leans

outwards and has been propped on the outside by a large wedge-shaped

block of concrete. [16 & 17] It is not known if the wall here

has been underpinned. This section is certainly in need of an engineers

assessment with a report on its stability. It may need urgent repairs

to prevent collapse. On this section and on the first two sections

there are long horizontal cracks on the inner side at the original

ground level and the weight of the upper part of the wall is hinging

over this point.

The polygonal tower is rounded in plan towards the outside and

three-sided towards the inner side of the wall. [18 & 19] Its

wall stands to 6.3 metres high on the outside and 4.3 metres towards

the inner side. On the inner side of the tower the ground level has

been lowered by 800 mm. A clear line for the earlier level can be seen

across the lower part of the flint work. Above this line the angles

of the tower are well built in brick.

[23-07 Tow Nor Elev] [23-08 Tow Wes Elev] [23-09 Tow Sou Elev] [23-10

Tow Eas Elev]

The tower was of two storeys with a lower and an upper chamber.

[23-11 Tow Nor Sec] [23-12 Tow Wes Sec] [23-13 Tow Sou Sec] [23-14

Tow Eas Sec] The lower chamber was entered from the inner lane of

the wall by a doorway through the central flat side of the polygon.

The doorway had a shaped brick head and part of the brick hood moulding

of the doorway survives. This doorway is now blocked and the tower is

entered by a breach on the south side which is secured by a modern iron

gate.[20 & 21]

The upper chamber was presumably accessed from the wall walk.

There is no evidence in the lower chamber for an internal staircase.

Internally the tower is 4.1 metres across and almost the same

dimension from the outer to the inner wall. In the lower chamber

there were arrow slits or loops on both the north and south sides

to look along the line of the outer wall. These were later made into

windows but are now blocked.

In the 19th century the tower was used as part of the accommodation

of number 80 Chapel Field Road with a kitchen on the lower level, reached

from the yard of the house by a doorway cut through the outer wall of

the tower. The outline of this inserted doorway survives on the outside

but it is now blocked. [22] Inside the tower, the present floor level

is about 300 mm above the pathway and it is tiled. Presumably this floor

survives from the period in the 19th and 20th centuries when the lower

part of the tower was a kitchen for the house facing on to Chapel Field

Road. It is unclear if the medieval floor level survives below this.

The upper chamber of the tower was also incorporated into the house

and a doorway, inserted at the upper level, can still be seen on the

south-west side of the tower but it too was blocked when the house was

demolished.

There is no indication inside the tower of the structure of the

medieval first floor. However, the upper part of the wall is narrower

and steps in on the inside and in the 19th century this ledge would

have supported a wooden floor. There is no evidence for vaulting in

the tower for either chamber.

The walling of the tower is generally in good condition. On the

outer face the mortar of the flint work is galleted. [23, 24 & 25]

South of the tower is a substantial section of wall some 25 metres

long. This stands 4.5 metres high, almost its full original height,

with clear evidence on the inner side for the level of the wall walk

and the lower part of the outer parapet wall survives though the top

has been much rebuilt and has lost all its crenellations. [26]

On the outside of the section can be seen the remains of 5 loops or

arrow slits. These are spaced irregularly and are much closer together

than loops on other sections of the wall. [27 & 28] The loops here

are between 2.4 and 2.8 metres apart. There is is now no obvious explanation

for this odd spacing of the loops. Possibly it suggests a sequence

of building where perhaps sections of the wall were constructed between

standing features but such a sequence could only be reconstructed if

there was an extensive archaeological investigation of the footings of

the wall on both sides. On the inside, apart from at the low south end,

there is no evidence for wall arches. [29]

At the south end the wall drops in height. Here there are the

remains of three arches. [30 & 31] In this section the wall is

at most a metre high and in parts the facing flints of the face are only

300 mm high (above the medieval ground level). Much of the wall here is

exposed core work.

The facing flint on the inside is in a relatively good state of

repair. There are a number of small blockings and patches with brick

though it is not known what these indicate or what they respect.

Several square blockings at an intermediate level look like beam

slots and there appears to be the horizontal scar of weathering for

a lean-to roof. However, map evidence indicates that in the 19th

century there were no houses against the inner side of the wall anywhere

along this section.

The medieval ground level has been lowered by at least 800 mm on

the inner side and the wall is now under built or in effect supported

on a retaining wall built in mauve bricks. This is the part where the

footpath is at its narrowest and on the factory side of the path there

is a boundary wall in the same brick which forms a kind of gully here.

Presumably the ground was levelled to produce an almost flat if very

narrow public path way. Photographs of the inside of the wall on either

side of the tower now in the collection at Garsett House show just how

much of a bank was cut away when the footpath was created. These

photographs are not dated but were probably taken in the 1960s.

There is a wide gap of just over 25 metres in the line of the wall

before the fourth section. Six complete arches in this section have

been lost. [24-02 Plan]

Principal conservation problems:

1. Settlement

At the north end of this section of wall the first two short

sections and the north end of the section with the polygonal

tower all have serious problems with poor or no foundations and

the removal of ground on the inner side. Documentary and archaeological

evidence [see Barn Road report] suggests strongly that this section of

wall was built on an earlier defensive bank. At Barn Road the new flint

wall was set on a relatively shallow foundation trench filled with

layers of flint and mortar. On the outside towards the ditch some

stability was provided by taking the wall down into the ditch - at

River Lane the outer side of the wall continues at least 2.4 metres

below the current ground level. On the inner side it was presumably

the bank, up to a metre high, that provided some support and some

protection from weathering. Where this bank has been removed at Coburg

Street the consequences are apparent. It is recommended strongly that

a specialist engineer's report is commissioned to assess and monitor

the settlement of the wall at the north end of this section. It is also

recommended that the bank should be reinstated for the whole length of

this section of wall.

2. Shedding flints on the face and top of the wall

Particularly a problem on the two north sections and on the top of

the wall to its south. The section with the polygonal tower is in a

good condition and has been repaired recently. Few flints are loose.

3. Intrusion of woody stemmed plants

Not as much of a problem as on many sections of the wall. Small area

of buddleia on the outer side immediately north of the polygonal tower

should be cleared.

Note: Since this report was drafted the trees have been removed but

this recommendation has been left in as the self-seeded trees and bushes

in the tower should be removed before they become established.

There are a number of well-established self-seeded bushes within the

polygonal tower and these should be removed.

4. Deterioration of the brickwork

This is a common problem throughout the circuit of the walls.

Once the wall walk deteriorates and collapses or in part collapses,

water gets into the core and the wall over the arches is particularly

vulnerable. The brick is relatively soft and once water penetrates

the brick work crumbles and breaks away. The arches at the south end

of this section have collapsed and no facing bricks survive. The

brick hood moulding on the blocked doorway on the east side of the

polygonal tower is in a poor state and much of the profile has been

lost. Bricks in the loops and putlogs, to some extent protected,

are in good condition.

|